Sports Capital 2018: Does Class Matter?

Sports Capital 2018: Does Class Matter?

In January 2020, the allocation of Sports Capital Grants made headlines across the country. With these allocations came moans, groans, cheers and praise for a grant system that is severely underfunded. However, the recipients of the grant money has caused much debate. Most recently, Mr Ewan MacKenna and Mr Philip Boucher-Hayes have inputted to the debate on Sports Capital Grants. Is it about “La-la Land” forgetting what sport really is? Or, do we all need a significant dose of reality? Mr MacKenna writes “To be fair to the sports grants system, that it exists is a step in the right direction. But how it exists is problematic.” The issue, though, is not how it exists, but rather the general Irish interpretation of the grants system. Over the past number of years, 2into3 has conducted research on Sports Capital Grants. As outlined in previous research findings, delving deeper into the figures better informs the debate. Questioning the allocation by quantum is not a fair assessment of the Department of Transport, Tourism and Sport’s (DTTAS) policy towards the allocation of Sports Capital Grants.

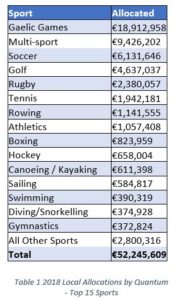

Following the fallout of the 2017 round, DTTAS followed through on their commitment to dedicate more funding to socio-economic disadvantaged areas. The system they have used for the more recent rounds was the Pobal Deprivation Index. Clubs that were based in disadvantaged areas, according to the Index, were given more marks than clubs not in these areas. Furthermore, the level of own funding required varied depending on your location in the Pobal Index. Clubs from disadvantaged areas were given greater preference. However, many have taken exception to the DTTAs allocation of money, see table 1.

Following the fallout of the 2017 round, DTTAS followed through on their commitment to dedicate more funding to socio-economic disadvantaged areas. The system they have used for the more recent rounds was the Pobal Deprivation Index. Clubs that were based in disadvantaged areas, according to the Index, were given more marks than clubs not in these areas. Furthermore, the level of own funding required varied depending on your location in the Pobal Index. Clubs from disadvantaged areas were given greater preference. However, many have taken exception to the DTTAs allocation of money, see table 1.

Use of the Pobal Index does not tell the whole story. DTTAS is very much so aware of this. A club sitting in a Pobal classified “affluent” area could have many members coming from disadvantage or minority groups. The same could be said vice versa. Greater consideration should be given to the member composition and catchment area of clubs applying for grants. However, at the time of writing, a more refined system has yet to be developed or suggested by DTTAS or the general public.

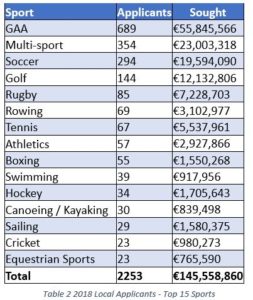

Mr Boucher-Hayes of Drivetime RTE Radio 1 argued that the grants “show a distinct bias in favour of middle-class sports.”[1] This was an argument put forward in previous rounds. DTTAS philosophy is quite simple, if you’re not in it, you can’t win it. It begs the questions, how can DTTAS allocate funding to those who are not applying for the programme in the first instance? A breakdown of table 2 shows what sports applied for the local fund in 2018. Why did the GAA receive the most? They applied in greater numbers. Why did golf receive more than boxing? Simple numbers, golf clubs applied at a rate of 3:1 compared to boxing clubs.

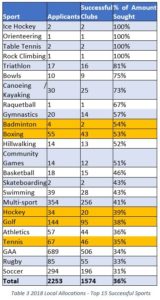

To secure a Sports Capital Grant, you need to be proactive, not reactive. Tennis Ireland has trained clubs to be proactive with Sports Capital. Unsurprisingly, tennis’ application rates increased and therefore what they received increased. Similarly, golf clubs have been trained to anticipate deadlines, not react. This approach does take time, though. 2into3 have done similar work with cricket, for example, which has seen a 17% increase in applications and an 83% increase in secured funding in 2018 compared to 2017. No sport will apply at a comparable rate to the GAA. The GAA is at the root every almost every community in Ireland. Nonetheless, it is the responsibility of national governing bodies to prepare and inform their club base appropriately. This is completely out of the control of DTTAS, it cannot force any club to apply.

For example, clubs that do not satisfy the land title requirements as stated above can still apply for capital. Most clubs either overlook this or are not aware of the opportunity. In fact, DTTAS increased the threshold from €25,000 to €50,000 in 2018 in a bid to increase applications of clubs that do not suit the title requirements of the programme. Furthermore, clubs can also apply for up to €150,000 in equipment grants with no need for land ownership. Almost half of boxing’s allocation came via the equipment grant route.Ownership of land is another critical issue to access of Sports Capital Grants, which the GAA has over others also. The fact remains that sports like badminton, basketball, boxing, squash, and more all play out of sports halls. Often, they do not own these sports halls or work off yearly rental agreements. To apply for a full maximum grant of €150,000, clubs either need own the land through freehold or have leasehold of a minimum duration of 15 years at the time of the application. The lack of applications from these sports would suggest that long-term agreements are in the minority. Admittedly, the statistics provided by DTTAS do not go deep enough to show how many boxing, basketball, etc clubs applied under multisport. The numbers are effectively skewed. However, the programme was adjusted in 2018 to encourage more clubs to apply for capital.

Furthermore, DTTAS gives preference to applications from local authorities to aid local capital development. Since 2014, DTTAS have shown a distinct preference to applications made by local authorities and local sports partnerships who are making applications on behalf of clubs unable to do so themselves. This included €97,850 to Ballymun Sports & Fitness and €94,500 to Finglas Sport & Fitness Centre. However, these applications are classified generally as “multisport” which was only bested by the GAA. “Multisport” facilities will not make national headlines as Irish society is too transfixed with looking over the fence to see how one sport did compared to another. Multisport facilities are commonplace across Europe.

Allocations to hockey have made significant headlines over the years. To put the 2018 allocations in perspective, that’s 1.3% of the total funding and only 39% of what the 34 hockey clubs asked for. On the other hand, boxing received 1.6% of total funding and 53% of what clubs asked for. Undoubtedly, boxing performed better than perceived “middle-class sports” such as hockey, golf and tennis. Should we simply exclude any sport based on public preference to others? No, DTTAS simply cannot do this. Clearly, an awareness campaign is needed to raise application rates among sports like boxing. One wonders, why doesn’t the Sports Capital Programme get such publicity when a funding round opens?

In the UK, much research was undertaken to prove the true impact of sport. The Culture and Sport Evidence (CASE) programme was a joint strategic research initiative led by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) and its sector-leading arms-length bodies: Arts Council England, English Heritage and Sport England. The published research provides ground-breaking evidence on making the case for investing in sport based on the broader wellbeing, health and educational outcomes. Some of the key findings were increases in numeracy scores, education, health gains and substantial long-term economic value in terms of avoided health costs. Furthermore, a “A range of factors, including age, gender, alcohol consumption, childhood experience of sport, socio-economic variables, a limiting illness or disability, educational attainment, unemployment, TV and internet use, and the proximity of local sports facilities, are directly associated with people’s participation in sport.”[2] It is time that studies similar to this are commissioned in Ireland.

When the whistle blows, there are always winners and losers. After all, it’s the basis of sport and an oversubscribed grant system is no different. Should funding be given to allow clubs access to land? Or should we follow the approach implied by Mr MacKenna and Mr Boucher-Hayes and simply expel “middle-class sports” from the Sports Capital Programme? A more pragmatic approach is needed, one that supports the grant system and gives evidence to DTTAS that €50m-€60m each year simply is not enough.

Understandably, calls for increased state support are no surprise; a common critique that could be used across every government programme and support. What makes Sports Capital any different? Frankly, it is the primary mechanism for clubs access significant capital funding. Without it, the provision of sporting developments at local level would effectively stagnate. The benefits of sport cannot be understated – it benefits physical, mental and emotion health. It helps social inclusion and cohesion. Na Fianna’s GAA club’s social value report gives hard evidence to the augmentation of state supports for local clubs. Now is the time to significantly increase the investment in grassroot sport. Valid applications under Sports Capital clearly have credit. The level of funding under Sports Capital should allow all valid applications to get support. This would benefit all sport – not just the reader’s choice.

For more information, please contact Patricia at patricia.keenan@2into3.com or +353-86-0657347.

[1] Philip Boucher-Hayes, Drivetime RTE Radio 1, Thursday 21 November, 2019.

[2] https://www.sportengland.org/our-work/partnering-local-government/tools-directory/culture-and-sport-evidence-programme/